The opening text from the ‘Oslo Futures Catalogue’, produced on the first ‘Strategic design for society’ course running at Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO), 2021

Einar Sneve Martinussen and I just posted about the Strategic Design for Society course that we’ve been running at Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO) for Masters design students. We focused on the students’ first assignment: producing an Oslo Futures Catalogue, a portfolio of ideas intended to contribute to, and counterpoint, the ongoing process of developing the city’s strategy for research, development and innovation.

Download the catalogue here

You can download a copy of the Oslo Futures Catalogue v1 (PDF) here. You can also read an accompanying ‘making of’ article on which goes into the methods taught and practices on the course, with some reflections on the students’ work.

It’s the first time we’ve run the course, which Einar and I taught with Ted Matthews and Aleksandra Zamarajeva Fischer, and this Oslo work was the first project on the course (the second addressed gender equity in societal planning for Karmøy municipality in western Norway—more on that later.)

We wrote an introduction to the Catalogue, framing the approach to the course, and its relationship to the city’s innovation strategy. That text follows, and works not only as a primer for the Catalogue but also for the course itself. As such, you can also take it as our initial, open contribution to the emerging set of academic courses beginning to coherently address strategic design theory and practice.

This course continues the work started a few years ago, with events like Digital Skølråderett and the student-produced book TRUST IS WORK, coming from Einar’s teaching and research exploring design for a digital Nordic welfare society. We also wanted to directly address ‘innovation’, an awkward and unhelpful word that is often used lazily, sometimes duplicitously, and generally narrowly. By pulling the question of innovation into the richness of everyday life, drawing from a sociological perspective as well as urbanistic, the students could explore perspectives that were both open and grounded, placing technology and economy into the broader context of urban culture.

This project was designed as a contribution to Oslo’s official innovation strategy, which was being developed in parallel by the city with assistance from D-Box, AHO, Rambøll and Halogen. The students explored and challenged the municipality’s existing societal plans and strategies through design, and presented their portfolios of ideas to senior municipal staff leading strategy, but we kept the work at arm’s length on purpose, building a creative buffer from the formal process. Yet—spoiler alert—it is fair to say that the students’ insights and contributions have been hugely appreciated by the municipality, and it will hopefully contribute to reframing aspects of the policy’s development.

Getting that relationship right is important: close, but also at a distance. Einar and I both believe that learning concerns practice, and that practice requires the constraints and possibilities of working with a ‘real world’ context, like a municipality and the work done in policy development. Being able to position the university close to the city in this way can be hugely beneficial all round. Amongst other things, universities are places that can both hold the public discussion about the future, and help shape it.

“Architects and planners, whether they design buildings, or recommend policy, are involved in doing. Therefore architectural and planning education requires training for doing.” — Denise Scott-Brown

We also try to be clear about what we talk about when we talk about infrastructure, building on some of the thinking I was outlining in my Slowdown Papers, positioned squarely in the context of social infrastructure, following Eric Klinenberg, Debbie Chachra, and many others. (There’s an emerging list of social infrastructures in the text below, co-produced with the students, which we’ll update, refine, and illustrate over time.)

In all this, we were drawn to Welsh sociologist Raymond William’s Keywords (1978) as a way of pacing out a wider territory, immediately looking to diversify the terrain that innovation strategies tend to reside in. Rather than sitting in the box that ‘technology’ is generally stuffed into, or myopically pursuing the last century’s economic growth logics, or being constrained by a disciplinary logic, this meant we could put urban culture to the fore. We could imagine an array of words, laid out over the eight weeks, and serving as prompts for a variety of questions. This allows a kind of kaleidoscopic interpretation of the subject, whilst nurturing a critical sensibility for everyday words about everyday life.

So these ‘keywords’ might include themes like innovation, infrastructure, technology, and some strategic design principles, like prototyping or Trojan Horses. But they would also include spatial organising principles like garden, block, city, or political structures or social concepts like municipality, community, rights, as well as cultural patterns, rituals or perspectives, like care, participation, celebration, hopes.

This melange of keywords enabled us to explore many different angles on the patches of ground and clusters of community that we call ‘neighbourhoods’. We chose neighbourhood precisely to be able to bring these questions to ground. This would give the students a scale they could engage with directly, whilst remaining ‘complex enough’, hovering in the space between buildings and city. It also links neatly to the Oslo Architecture Triennial 2022 and its Mission Neighbourhood, with which we are also happily implicated.

(We could also elide some of Williams other works with Lefebvre, who will be referenced below. As I’ve written elsewhere, Williams’s sense that ‘the everyday’ is constructed just as art is conjured is a powerful idea to work through with architecture and design students. In The Long Revolution (1961), Williams writes: “Everything we see and do, the whole structure of our relationships and institutions, depends, finally, on an effort of learning, description and communication. We create our human world as we have thought of art being created.”)

The course format was, loosely, a day of lecture, seminar and discussion oriented around one of these ‘keywords’. More details below, and in this accompanying post which covers the framing that the lectures and discussions lent to the practical studio work. The rest of the week was studio time in which students could develop ideas for the Oslo project, with an emphasis on the generation of diverse array of ideas, seeding ‘a garden of possibilities’ rather than focusing in on one or two interventions. (Covid-19 hit the possibility of true studio time, unfortunately, but the students worked hard to overcome this.)

Students work in pairs or small groups as design is a team sport, an intrinsically collaborative discipline. We had several external contributors in addition to the teaching team of Einar, Aleksandra, Ted and me, as the accompanying ‘making of’ post describes, including guided walks and field research.

In all of this, as Master of Design students, the teams were able to move from analysis to synthesis, from keywords to imagery, from insights to concepts—in the language of the Catalogue: from What is? to What if? Given the short time frame, the range of ideas and the verve and richness with which they are produced is a delight to see—again, as the ‘seeds’ of ideas, to be developed.

As with any first run of a course, one discovers numerous things to do differently next time. More to follow on that. We want to lift questions of urban technology more, for instance. We put this on the table at the start, but it was not really picked up—which is not a criticism of the students, to be clear. To see, as the text states below, that a shared autonomous ferry, for example, can now be understand as social infrastructure just as a shared garden or community library might be, with the dynamics of distributed technologies unlocking entirely new modes of ownership and operations requires a reframing of infrastructure just as much as a more nuanced understanding of technology than is commonly used in this context.

We will also want to dig further into questions of value—particularly with municipalities like Oslo Kommune in mind, who will need different models, outside of traditional Nordic procurement cultures, for undertanding value in a more holistic sense: flipping maintenance into care, for instance, or liability becoming learning. As well as Mariana Mazzucato’s rethinking of value at the macro scale, the recent work of my long-time colleague Justin O’Connor at the University of South Australia, looking at the entanglement of culture and economy, culture and everyday life, and the new possibilities in ‘foundational economies’, maps onto the interests outlined here, concerning the social and cultural infrastructures of everyday life in the city.)

But equally, AHO is the Oslo School of Architecture and Design, and when the course runs next time we want to dig further into the productive, contested space of that ‘and’ between architecture and design. There is another version of the following text, which begins to more thoroughly explore what’s happening in this third space between architecture and design (a perhaps distracting enquiry that few outside of these fields may care about, to the extent that it sometimes has me recalling the lovely put-down: “Like two bald men fighting over a comb.”)

We realise that taking final year students from a degree based in service design, interaction design, industrial design, and systems-oriented design, and then setting the controls for the heart of The City, without moving through several years of architecture and planning, would have both advantages and disadvantages. In a sense, we are working with urbanism as a perspective and practice, recalling Keller Easterling’s apt description of the urbanist as having almost a ‘canine mind’ or sensibility, concerned with observing and addressing the relationships between things in the city, their very disposition. You’ll see the reference below.

This relational approach maps onto our understanding of infrastructures, as the connective tissues beneath and between other structures, and of neighbourhoods themselves, as assemblages of relationships; fixed and dynamic, material and ephemeral, social and political. It also places everyday life squarely in the frame. Design’s facility with field research, user research, prototyping, and everyday touchpoints, as well as being attuned to social relationships, organisational contexts, and political and economic structures, has much to offer architecture. But equally, there are, of course, significant issues that emerge if architecture’s depth and breadth, as well as aesthetic and spatial sensibilities, are not present and active. Above all, it is architecture’s ethical responsibility for the city that the public context of strategic design must bring to the fore.

We see these futures catalogues as ‘gardens of ideas’, as they are more akin to seed banks than design specifications. They require, or even demand, tilling the soil, cultivating, companion planting, nurturing, harvesting, propagating, using. As we discussed with the students, the idea of the shared garden, whether in the city or elsewhere, is both everyday and radical, literal and metaphorical, formal and informal, as we can see in the thoughts and practice of Rebecca Solnit, Jamaica Kincaid, Ron Finley, Leon van Schaik, Masanobu Fukuoka, Walter Hood and Grace Mitchell Tada, Linda Tegg, Emma Marriss, Julian Raxworthy, Dan Pearson, Derek Jarman, Robin Wall Kimmerer, and indeed Solnit’s recent book on George Orwell’s gardening. This was a quick attempt at a first planting, by a talented group of students. Let’s see what sprouts, and what new gardens to plot out next.

Teachers: Einar Sneve Martinussen, Dan Hill, Ted Matthews and Aleksandra Zamarajeva Fischer.

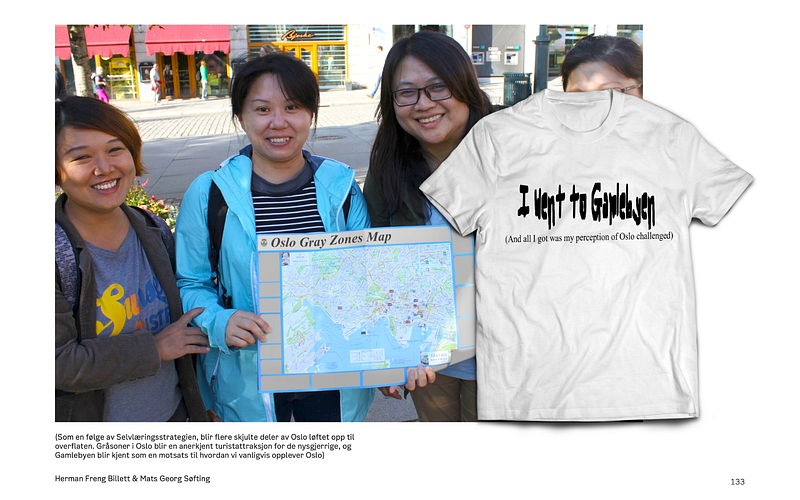

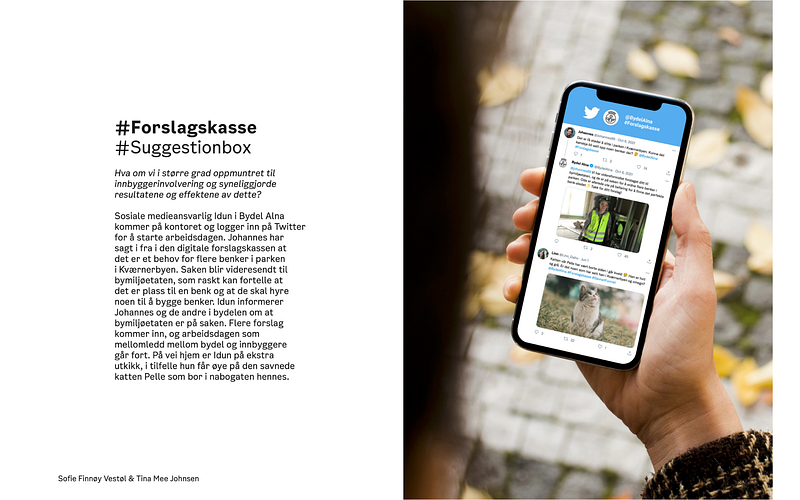

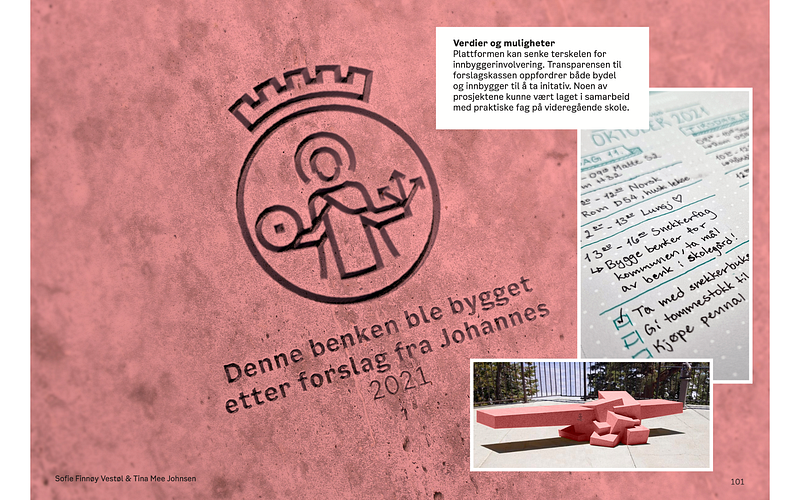

Students: Pernille Hartvigsen, Cornelia Schmitt, Kamilla Bedin, Herman Freng Billett, Kristin Mar!e Brudeseth, Johanna Sofie Brämersson, Tina Mee Johnsen, Sigrid Løvlie, Nikolai Sabel, Åse Lilly Salamonsen, Lisa Siegel, Elizabeth Bjelke Stein, Glenn Sæstad, Mats Georg Syvertsen Søfting, Sofie Finnøy Vestøl & Anna Malene Vik.

Download: Oslo Futures Catalogue v1 (PDF) (the text in the Catalogue is an instinctive mix of English and Norwegian! But translate tools work quite well.)

What follows is the essay that opens the Catalogue, and frames the approach to the course and the work within:

Exploring Oslo’s innovation strategy through design

The Oslo Futures Catalogue is a collection of observations and propositions describing possible futures for neighbourhood life in a more innovative Oslo, created by design students on the Strategic Design for Society course at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO). The Catalogue comprises a collection of ‘What is?’ observations drawn from explorations of everyday life in some of today’s Oslo neighbourhoods, from which a set of ‘What if?’ propositions have been invented or uncovered. These are imagined as possible urban futures, and articulated as a portfolio of new or alternative social infrastructures at the neighbourhood scale. The Catalogue dwells on ‘the everyday’ in these neighbourhoods, both real and imagined, in order to help ground Oslo’s strategy for innovation in the soft city we all inhabit and co-create. This helps place innovation, whether technical or social, in the context of the lived city, its nature and human nature, its politics and places, its constraints and possibilities, its histories and futures. Although no more than a start, we hope that it complements, enriches, and extends how Oslo can think about innovation in meaningful and actionable ways.— Dan Hill and Einar Sneve Martinussen

In the Autumn of 2021 AHO and D-Box — the National Centre for Transforming Public Services, together with Rambøll and Halogen, ran a project for the Oslo municipality about developing a strategy for research, development and innovation. To complement this project, AHO ran an experimental, practice-based design research process, which produced both insights and propositions exploring the idea of the innovative Oslo neighbourhood. The outcome of this process is the Oslo Futures Catalogue (PDF), which can be understood as a creative, explorative complement to the work being conducted by the city, and its consultants Rambøll, Halogen and D-Box. It looks to offer up different thoughts and perspectives on the same city and the same theme, trying to enrich and support the strategy process.

Students and design researchers from AHO’s ‘Strategic Design for Society’ course conducted a study that locates questions of innovation in the everyday life of Oslo’s neighbourhoods. This context helps ground questions of new technologies, cultures and approaches, whilst still exploring or uncovering a portfolio of possible futures, framed around the idea of new or alternative social infrastructures.

This continues AHO’s research and practice into design methods and innovation in the public sector, with a focus on futures and citizen-centred design of infrastructures and services, places and policies. This design process is a form of ‘future faceting’, which looks to explore and visualise various ‘facets’ of everyday life, using creative and analytical tools from interaction and service design, such as user insight, visualisation and prototyping, within elements of strategic foresight frameworks and urbanism.

AHO students used this method to explore and challenge what life could be like in a future Oslo framed around Oslo’s strategic goals of becoming greener, warmer, more creative and inclusive. Qualitative observations of today’s everyday life — the ‘What is?’ — are used as a basis for understanding and speculating about these facets. Then, rather than attempt to design apparently complete systems, which can encourage flawed or narrow predictions, the students have instead created glimpses of near-future Oslo neighbourhoods, arranged in a catalogue of about 70 mini-scenarios. These glimpses draw out aspects of everyday life, such as upbringing, growing old, community life, social innovation, and retrofitted and sustainable places and spaces. The window for these glimpses is the ‘future around the corner’ as well as the observations and insights drawn from today’s neighbourhoods, anchored in the inhabitants’ lived experience of the city, recognising the value of working with the city we have, whilst also describing the possibilities in adaptation and regeneration.

Nonetheless, this innovation method allows for creative, opportunity-based design development, neither stuck in problem-oriented mode or caught in solutionism. The work produces a diverse portfolio of near-future glimpses — the ‘What if?’ — suggesting a diversity of future scenarios. This constellation of evocative ideas can be used to illuminate opportunities across culture, technology, sustainability, community, and governance, and so help cultivate a richer set of possibilities latent within the city’s future.

The ambition with this broad exploration has been for design to make visible and contextualise what innovation can contribute to Oslo, when placed in these more complex assemblages of people and place, culture and community, tech and infrastructure. These design experiments have helped inform the AHO’s researchers’ advice to the strategy process, but they can also be seen as direct contributions to the process in themselves, and as an implicit suggestion to use such design methods in forthcoming strategies for research, development and innovation.

Challenging urban innovation

‘Innovation’ is an awkward, loose, and problematic word, particularly in the context of cities. It is often worryingly absent of critique, approached as if an unalloyed good. Yet the last years of innovation in urban technology indicate that it can be anything but. Ride-sharing companies, having initially promised a reduction in traffic, produced exactly the opposite, whilst introducing a range of other problems to boot. Services offering easy, temporary leasing of apartments and houses have tended to increase rents in cities with existing housing affordability issues. E-scooter companies bring joy, fun, and easy movement to city streets, yet can end up awkwardly occupying broadly-shared public spaces for a relatively narrow audience. E-commerce offers convenient shopping for many, whilst also decimating physical retail and increasing logistics traffic in cities. Social media drives much community-led action and activism, yet can also sow the seeds of damaging division, entirely outside of meaningful democratic engagement. Surveillance tech, which increasingly moves beyond social media to include face-tracking cameras and robots, might be shredding civil rights beneath its purported ambition to make urban living safer or more convenient.

Equally, although the city is a shared condition, the financing that drives these innovations is not. And so, the return on these investments is not distributed widely at all, whilst its impact is. The idea of the city as a public good, or an assemblage of shared and commonly-owned rights, assets and possibilities, can quickly fade under these barrages of ‘innovation’.

At the same time, some cities have matured beyond the growing pains of the first so-called ‘smart cities’ strategies. An inventive and progressive Barcelona is developing city-owned energy companies, car-free and green Superblocks, and advanced forms of citizen participation. Melbourne grows its urban forest canopy to heal the city, via both trees and tweets. Taiwan has advanced tech-for-good communities as well as powerful capabilities within its government, with their 3 F’s approach to civic tech — “fast, fair, and fun” — increasingly influential. Paris places participatory budgeting alongside its increasingly participative and sustainable urban realm, framed around its 15-minute city model.

A broader, deeper and more sophisticated approach to innovation, which puts technology, infrastructure and change in the context of everyday life, of civics and politics, of nature and human nature, is slowly beginning to emerge. As Brian Eno (2021) put it, when writing design principles for Vinnova’s Swedish Streets mission: “A really smart city is the one that harnesses the intelligence and creativity of its inhabitants.” These ‘inhabitants’ might increasingly be understood to include a broader biodiversity, encompassing other forms of nature, and of nature-based technologies, as well as people, but taken alongside Eno’s other suggestions, the emphasis is clearly on urban culture.

And so to Oslo, with its combination of an ambitious urban trees strategy and car-free city centre, linked to broadly sustainable approaches to energy, housing, and mobility, and building on a traditionally progressive, trust-based ‘Nordic model’ foundation. These themes sit within broader explorations of designing for ‘digital urban living’, previously developed in work at AHO, with associated events like Digital Skølråderett, or ‘design for a Nordic digital shift’.

A creative, practice-led school like AHO is a place that can both hold the discussion about the future of the city, and help shape it. Design students and researchers at AHO can constructively critique ‘urban innovation’ by bringing it to life, by understanding it, shaping it, and testing it in context. Design is about new cultural imaginations, about invention, about ideas. Yet equally, design also brings form to ideas. It translates our values as a society into the hard and soft infrastructures of everyday life. It grasps that floating abstract word “innovation”, and wrestles it to the ground, making it tangible, accessible, meaningful, dropping it into a context of people and place. In this urban context, innovation only qualifies as innovation when it actually touches the ground, hits the streets.

“It is architecture and design’s task to give form to a societal idea (like justice) through the creation of a setting for people to encounter that idea (like a courthouse). We see in our public buildings and spaces (our park benches and metro trains; a hot dog kiosk and a monument to the dead) what we are made of. Design can not avoid this assignment -it either embraces the task, or it unwittingly displays, or even conceals, society’s prejudices and weaknesses.”— Kieran Long, Public Luxury exhibition catalogue, ArkDes (2018)

The point of this project is to understand how innovation translates into everyday life. How might contemporary innovation shift our everyday environments in Oslo, like the neighbourhoods we inhabit and the social infrastructures that glue them together? How does this help us understand, articulate and inform the society that such innovations and infrastructures produce?

In essence, the students have made a catalogue of possible futures, not as predictions or goals, but as markers of possibility, a way of broadening and enriching the sense of what Oslo can be about, and how to see the city as culture, in most senses of the word, rather than simply inert structures of buildings and infrastructures.

Another design principle Eno lent is “Think like a gardener, not an architect: design beginnings, not endings.” So this catalogue is a garden of ideas, seeds to be cultivated and nurtured and adapted over time, to generate life, as open beginnings full of potential, rather than the closed ending of finalised and signed-off plans.

Approach: Strategic design for society

The Oslo Futures Catalogue comes out of a case study from a new course at AHO, Strategic Design for Society (2021), running through the autumn term in the final year of the Master of Design. It has a focus on strategic design in the broader context of societal development.

“Strategic design takes the core principles of contemporary design practice — user research and ethnography, agile development, iterative prototyping, participation and co-design, stewardship, working across networks, scales and timeframes — and then it points this toolkit at ethical concerns, addressing systemic change within complex systems, and broader societal outcomes.”—Dan Hill, Strategic Design for Public Purpose (2019)

By placing design in this context, the practice of strategic design aims to enrich both policy and delivery concerning our shared systems and cultures as well as shared challenges. Strategic design has emerged and consolidated over the last decade, with the Nordic region often forging this new ground: from Helsinki Design Lab in Finland, Mindlab and Danish Design Centre in Denmark, and the recent work of the strategic design function at Vinnova in Sweden. In Norway, in the context of this project, strategic design builds on AHO’s previous work, as the research group Digital Urban Living, as well as AHO’s involvement with D-box, the National Centre for Transforming Public Services, and DOGA. Globally, strategic design is increasingly part of wider public sector innovation developments, building or re-building design capability in governments from Singapore to Scotland to Santiago, or at the European Commission’s Policy Lab in its Joint Research Centre (and initiatives like New European Bauhaus), whilst also fitting broadly into context of the ‘entrepreneurial state’, after the economist Mariana Mazzucato (2013).

A crucial aspect of strategic design is engaging with politics and policymaking, the so-called ‘dark matter’ that shapes the designed living environment as much as advances in materials and tech do. And so the course also works directly with municipalities, in 2021 with Oslo and Karmøy. This allowed students to begin to explore real-world contexts and their governance, steering and shaping, building up an understanding of each living environment and the aspects of culture, community and institution that frame what happens there.

From these design-led investigations, the students find a position on the place, and its potential for change, and the nature of that change. The students articulate these findings and extrapolations through portfolios of examples of possible futures. This catalogue portrays that portfolio for Oslo, as well as reflections on the work.

As the duration of the investigation was eight weeks, this was a necessarily speedy piece of work. The emphasis was on producing a breadth of ideas — that diverse portfolio of propositions — rather than a few deeply-considered proposals. Strategic design’s sensibility and stance involves zooming back and forth between the details of interactions, services, infrastructures, and built and living environments, and the wider social, organisational and political context that these things sit within — from the door handle to the city plan, and back again. The students’ practical work was supported by seminars covering new forms of value, organisations, skills and perspectives, or delivery techniques, which would be necessary if processes such as these were to be embedded in a municipality.

Although the course did not approach architecture directly, there are strong elements of urbanism at play here. Keller Easterling (2021) describes the kind of ‘urbanist’ that was being encouraged here, a role somehow sitting between architect, planner, designer, sociologist, botanist, historian, detective, novelist and journalist:

“An urbanist, with something like a canine mind, observes the city as a collection of reactive or interdependent components. It is easy to see the choreography of moving parts like cars and pedestrians as they synchronize and intersect. But urbanists look at urban spaces like streets and assess potentials even in the relationships between their static solids. An ethnographer may interview the inhabitants. An economist may gather data about livelihood. But an urbanist observes an interplay of physical contours that are also expressing limits, capacities, and values …Urbanists may observe the relationship between a traffic light, a business that offers coffee in the morning, and a set of buildings that have inhabitants who care for the street. And they can see the matrix of exchanges between a subway stop and a giant building with a huge volume of inhabitants. Not morphology alone, but the interaction between components, determines the richness of this loose and changeable assembly of parts. There may be no set structural rules and few determinants — only some dynamic markers of changing relationships.”—Keller Easterling, Medium Design (2021)

Easterling describes these relationships as “‘disposition’… a property or propensity within a context or relationship … The disposition of any organization makes some things possible and some things impossible.” Easterling’s ‘disposition’ has analogues with the practices of service design, which look not only to understand and articulate ‘touchpoints’ within a multi-layered product, service or environment, but also the organisational context that makes that happen, as well as the strategic design focus on ‘dark matter’ and ‘the architecture of the problem’, that which makes some things possible in the ‘matter’ and some things impossible. The students were helped to cultivate these urbanist-like activities by the local architecture office Speed Architects, who led a guided walk through several Oslo neighbourhoods from the inner city up through the Grorud valley, identifying and discussing possible histories and latent futures, relationships and ‘disposition’ between organised local elements.

Approach: Everyday life

The 2018 Oslo societal plan ‘Our City, Our Future’ — summarised as “a greener, warmer and more creative city with room for everyone” — provided the context for the work, and the innovation strategy development sitting behind it. This strategic societal plan was discussed, and unpacked, with the students:

- Greener: softer, porous, cleaner, biodiverse, fit, pollution-free, regenerative

- Warmer: convivial, social, friendly, cozy, close, fun, prosocial

- Creative: creating, diverse, stimulating, open, fluid, reflective, resource-ful, productive

- Room for everybody: accessible, open, just, shared, diverse, adaptable

The students used these starting points to inform action-based design research, identifying multiple, diverse perspectives and propositions — the ‘What is’ and the ‘What if?’ — through which the innovation strategy might be grounded in Oslo’s everyday life.

The work of influential urban theorist Henri Lefebvre emphasised the sociological concept of ‘everyday life’, through which he discussed how the production of space creates frameworks for social, public and political life (1991). In order to explore societal change today, we examined how our environments — digital, service-led, physical, natural — are designed and structured, in order to better understand how these affect and shape everyday life, and the possible alternative ‘everydays’ latent with them. This approach has parallels to the traditions of progressive architectural practice and critique in the Nordics and other social democracies elsewhere, such as in the movement for social democratic housing reform and civic architecture, running in the region through much of the 20th century. This is a history that illustrates how a critical, yet constructive, approach to modernisation of society can be grounded in a qualitative examination of both everyday social needs and a participative agenda, as well as the potentials of engaging with new materials, technologies and industries.

Choosing everyday life, and its attendant design disciplines, as an approach to societal change has two purposes in this course: First, it represents an approach for exploring the everyday and experiential qualities of being citizens in a city, and participating in society. The everyday perspective, through concepts such as Lefebvre’s ‘right to the city’, also offers ways of contextualising and challenging many current trends, such as the more recent tech-led innovation models described previously.

Second, design methods and practices represent fruitful ways of envisioning, discussing and participating in broad arrays of possible futures. Design is typically a propositional practice based on research. As such, it can be used for meaningful, constructive, participative, and generative critique. Its sense of possibility can be highly adaptive, malleable. It concerns making, and as David Graeber pointed out, “the ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make, and could just as easily make differently.” What has been designed can, by definition, be re-designed, and these alternative possible futures can not only be proposed in highly tangible forms, but via methods like participative design and prototyping, be tested and refined in real world contexts, the lived experiences of the everyday.

We are surrounded by these design decisions. They include the obvious signatures of design — Oslo City Hall, or the city’s Opera House — but perhaps more influential, and certainly more used, are those quiet, mundane objects, spaces and experiences that suffuse every aspect of our neighbourhoods.

“The environment hosts dormant sculptures, bound to their context by clear, definable functions. We experience these sculptures every day in our mundane acts of life. These “sculptures,”or “things” are objects omnipresent in the built environment.They are often ignored, but, in most cases, they are all we have: power boxes, light posts, stop signs, curbs, gutters, and street signs. At the larger scale, the freeway or overpass are axiomatic structures. To see them clearly and become conscious of their material possibility, their normative functions must be disregarded. Attention to the everyday and mundane recognizes what already exists around us, and activates the space between its “things” and its people. Activating the mundane is an opportunity to see and experience the beauty and utility of the things in our life.”— Walter Hood & Grace Mitchell Tada, Black Landscapes Matter (2020) (Emphasis added)

Design disciplines provide us with analytical lenses that foreground perspectives on everyday life, as well as opening up for creative re-interpretation of existing structures, by engaging with this everyday reality around us: its touchpoints, environments, and infrastructures. Across the Nordic region, one can find rich historical traditions of progressive design, architecture and urbanism that have been involved in shaping the welfare state’s technical and social infrastructure (such as town plans, community centres, libraries, housing etc.). And as these infrastructures are now digital as well as physical, the way that urban technologies are articulated also describes what we stand for.

This emphasis on grounding research in everyday life has a long tradition in design, as well as the humanities more broadly, particularly sociology. From a design perspective, addressing the architecture of Gallaudet University’s campus, oriented around deaf people, Sara Hendren (2020) writes that:

“Imagine the envelope being drawn up from the ground, sides and corners and rooftop to form a shape around a series of habits and patterns for living that deaf people have been doing forever — a housing for the extant subtleties of these ways of being.”— Sara Hendren, What can a Body do? (2020)

We are interested in such ‘habits and patterns for living’ in Oslo neighbourhoods, and better understanding how they might be seeded with different potentials in order to address inequalities — environmental, social, or otherwise — whilst sketching out how the idea of Oslo as “greener, warmer, more creative and more inclusive” might help articulate the potential of the Nordic city as a public good.

The glimpses in this catalogue begin to bring form to these ideas, drawing up such envelopes from the ground, around the patterns of everyday life.

Approach: Social infrastructures and neighbourhoods

We asked the students to focus on social infrastructures within neighbourhoods, as key nodes in this idea of “everyday life”. We gave them the brief of suggesting how such infrastructures might be re-imagined in the context of a more innovative, future Oslo, and in doing so, to articulate what they might stand for.

Social infrastructures are core elements of a neighbourhood, in terms of both everyday life and innovation. Innovation relies on bringing new things together to create value. Infrastructures literally means the structures beneath things, the supporting glue, substrate, or binding medium — the things which bring things together.

Yet the understanding of infrastructure is increasingly broadening and diversifying, just as the arena of everyday life is, as the architect and urbanist Keller Easterling (2014) has made clear. She writes:

“The word “infrastructure” typically conjures associations with physical networks for transportation, communication, or utilities … Yet today, more than grids of pipes and wires, infrastructure includes pools of microwaves beaming from satellites and populations of atomized electronic devices that we hold in our hands. The shared standards and ideas that control everything from technical objects to management styles also constitute an infrastructure. Far from hidden, infrastructure is now the overt point of contact and access between us all — the rules governing the space of everyday life.”— Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft (2014) (Emphasis added)

This broader definition, beyond freeways and fire hydrants, better captures the context of everyday life today and tomorrow, articulated via digital-physical infrastructures, Yet even in the ‘previous’ definition of infrastructure, we can see these broader ideas: that infrastructure tells us what we stand for, and as Debbie Chachra (2021) describes, this means that they are laden with social and political meaning.

“Water treatment plants are a physical instantiation of the idea that politics are the structures we create when we are in a sustained relationship with other people.”— Debbie Chachra, Care at scale (2021)

The distinct notion of social infrastructures further reinforces this, further enriching the concept beyond Easterling’s digital network infrastructures or logistics protocols, or Chachra’s water treatment plants. The ‘social’ in social infrastructures emphasises connection and collaboration, conviviality and culture, these core building blocks of community, and neighbourhood. In Palaces for the people, Eric Klinenberg defines social infrastructure thus:

“The physical places and organisations that shape the way that people interact … the physical conditions that determine whether social capital develops. When social infrastructure is robust, it fosters contact, mutual support, and collaboration among friends and neighbors; when degraded, it inhibits social activity, leaving families and individuals to fend for themselves … crucially important, because local, face-to-face interactions — at the school, the playground, and the corner diner — are the buildings blocks of all public life.”— Eric Klinenberg, Palaces for the People (2018)

And as Alan Latham and Jack Layton (2019) state, “Cities need social infrastructure. Cities need places like libraries, parks, schools, playgrounds, high streets, sidewalks, swimming pools, religious spaces, community halls, markets, and plazas not only because of their practical utility but also because they are spaces where people can socialise and connect with others. These spaces matter.”

Yet it’s this expanded definition of infrastructure — networks, utilities, buildings and services, all of which are social, cultural and political in varying ways — that is fundamental to cities. We argue that all of this can be seen as social infrastructure. With the students, we explored how infrastructural elements previously ‘outsourced’ beyond the reach of social life — energy grids and other utilities, mass transit networks, construction, parks and municipal gardens — are now increasingly becoming distributed, participative and social systems, due to trends in both technology and culture. A renewable energy microgrid embedded in a cooperative housing block and integrated with electric shared mobility is clearly social infrastructure as much as it is energy utility, vehicles, digital services or architecture. As these services and spaces knit together, integrated alongside others, they potentially form innovative assemblages fusing together to create entirely new types of neighbourhood, new patterns of culture and community, and new forms of urban life.

A successful innovation strategy for a city will need all of these aspects in play; in other words, it will need as much meaningful, open, adaptive, and well-maintained ‘substrate’ as possible, providing the ‘loam’ for creativity, as well as the provision of sustainable, regenerative urban, civic, and natural elements that life is propped up upon. This is a fundamental shift in understanding of infrastructures, and their importance, and how city governments might think, and act, about it.

This short six-week sprinted project cannot pursue this potentially transformative agenda that deeply, but we wanted the students to develop this expanded definition of social infrastructure, and thus begin to embody the idea of this expanded practice. As part of the setup, the students conducted a kind of audit of social infrastructures, building out the following list:

libraries and laundrettes, plazas and playgrounds, pools and pavements, pizzerias and parks, pubs and bars, schools and streets, museums and markets, cafés and churches, barbers and nail salons, hardware stores and street vendors, studios and workshops, coop housing and courtyards, theatres and cinemas, community gardens and skate parks, bike sharing and dog parks, shared scooters and shared logistics, kiosks and kindergartens, docks and riversides, microgrids and community recycling, bike lanes and bus stops, promenades and woods, street furniture and sports grounds, community centres and aged-care centres, e-commerce drop-offs and car parks, bike racks and scooter stands, public transport and public toilets, public charge-points and trains stations, saunas and baths, drinking fountains and flowerbeds, performance stages and bandstands, wayfinding and shared noticeboards, public grills and viewpoints, cemeteries and civic plaques, steps and staircases, maps and municipal digital services, participation toolkits and ping-pong tables, chess boards and urban screens, greenhouses and abandoned buildings, playing fields and public university campuses …

This continually-updated list gives a sense of the diversity of social infrastructures we see in neighbourhoods. (This exercise also draws from the Incomplete City studio format, devised at UCL Bartlett and University of Michigan.)

Formed as a byproduct of field research, this emerging index provided the basis for the ‘What is?’ cataloguing of observations and insights. Yet it also, to some extent, begins to evoke a neighbourhood, constructed as an assemblage of these elements at the neighbourhood scale. Of course, cities, districts, neighbourhoods, and even streets and buildings, are greater than the sum of these parts. To paraphrase Jane Jacobs, a city is not just a big village. The urban condition is something other than a list of its elements; it has its own, in her words, “weird wisdom”.

Yet this focus on fundamental everyday elements, and the complexity of their shared conditions, provided a meaningful entry point for AHO students and designer researchers, just as it would do for Oslo municipality.

The neighbourhood emerged as the urban ‘unit of measurement’ for the course in part due to an increased focus on this scale in urbanism generally. The Oslo Architecture Triennial 2022 (OAT) is organised around a ‘Mission Neighbourhood’, and have a similar starting point to the AHO course (built partly on early engagement and collaboration between AHO and OAT):

“What do we mean by “neighbourhood”? Neighbourhoods represent the sum of everyday places we share with one another: The streets, squares, bus stops, kindergartens and schools, the places where we shop and meet — when possibilities allow. The neighbourhood is where communal activities take place. But it is also the context where the structures of society at large are expressed. The neighbourhood scale reveals our ability as a collective to handle challenges and create meaningful frameworks for everyday life.”—Oslo Architecture Triennial Mission Neighbourhood (2021)

This sits within a broader context of Paris’s 15-Minute City strategy, Barcelona’s Superblocks, Sweden’s One-Minute City street retrofit projects, Bogotá’s Barrios Vitales and Care Blocks, Portland’s Complete Neighbourhoods, Melbourne’s 20 Minute Neighbourhoods, Ottawa’s 15 Minute neighbourhoods, Shanghai’s and Guangzhou’s 15-Minute Community Life Circles and Chengdu’s 15 minute-oriented Great City plan, and so on. All of these, to varying extents, take the neighbourhood scale as their loose organising principles. Given this burgeoning interest and activity, selecting a similar focus for Oslo enables a useful comparison and counterpoint, as well as a meaningful scale to explore these questions of ‘everyday life’ and ‘social infrastructures’. And crucially, it is a scale that the students could explore and engage with directly, in grounded fashion.

The Oslo Futures Catalogue should not be read as a list of elements, constructing a single typical Oslo neighbourhood as if simple, additive building blocks, but rather a set of possible mutations in the code, or and perturbations in the patterns, of everyday life. Variants in codes, as we have learnt over the last two years, can generate complex new strains of urban living, adapting to changing conditions and thriving in the gaps, at the edges. Some of the examples that follow will occupy those niches, exploring edgier territory. Others will be simple extrapolations of apparently mundane activities, services, or spaces. These were ‘re-framed’, referencing Kees Doorst’s work: “What if a laundrette …?” “What if this abandoned building…?” This re-framing of everyday infrastructures can be highly generative and imaginative, whilst also, somehow, possessing a necessary pragmatism.

“The familiar that is a little off has a strange and revealing power.”—Robert Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown & Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas (1972)

All of the examples can be mapped back onto observations of today’s Oslo neighbourhoods — the What is? — and all of them then extend into possible futures — the What if? — some of which are overtly radical, and some of which are entirely everyday, and some of which strive to uncover or invent the radical in the everyday.

The Oslo Futures Catalogue: A portfolio of glimpses of possible neighbourhoods in an innovative Oslo

The Catalogue describes how new, or re-framed, social infrastructures might be articulated in everyday life in possible future Oslo neighbourhoods. It has two sections:

- What Is? (Articulated observations)

- What if? (Glimpses of propositions)

Although the format of a catalogue provides a useful constraint for communication, the students were introduced to various forms of narrative representation during the course, drawing from speculative design, paper architecture, graphic novels and cartoons, films and games, and so on. With the idea of ‘the glimpse’ and ‘the future facet’ in mind, this meant they could focus on conjuring more of a ‘mood-world’, to borrow Ben Highmore’s term, rather than attempt to produce detailed service blueprints, architectural plans and elevations, deeply-researched user journeys, or equivalent.

Rather than selecting one idea to dig into, the direction was to produce a diverse array of observations and propositions, a rich catalogue of possibility which others might draw from, build with, expand, adopt and adapt to their own needs. These are seeds to be combined in more resilient companion planting, rather a monoculture.

What is? Observations of everyday life in Oslo neighbourhoods

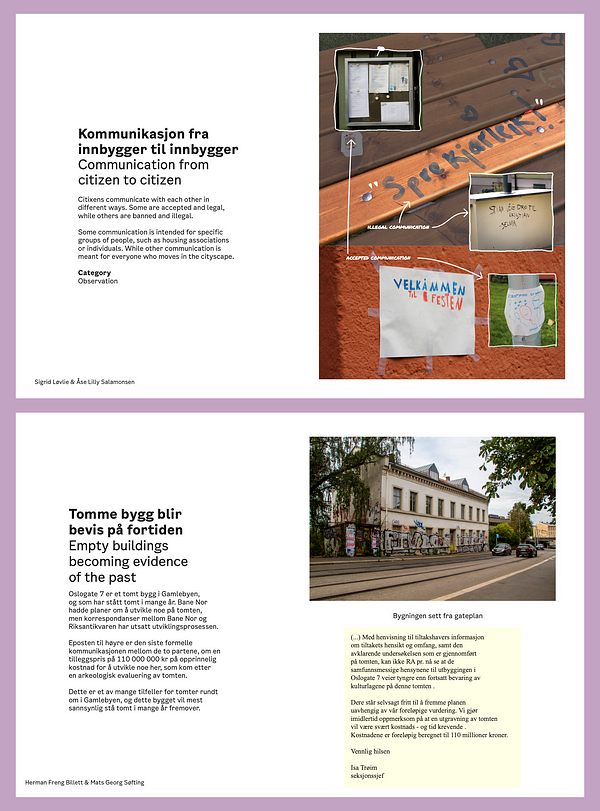

The first sets of observations focus on simple, shared infrastructures — such as laundries or tool sheds, playgrounds and riversides, bike parking and footbridges — as well as some of the ‘patina’ of the use, relating insights into how local people engaged with them. They also describe dedicated notice-boards and meeting places, as deliberate touchpoints for community, beyond those utilitarian functions.

The use of disused buildings or temporarily defunct spaces and infrastructures, amidst patterns of gentrification and regeneration, was particularly interesting, revealing the ‘spare room’ that cities always have, but rarely find ways to activate meaningfully and equitably. Some observations clearly critique new developments, whilst others question the integration of social housing into gentrifying neighbourhoods — or rather, vice versa.

Patterns of ownership and belonging were also spotted and described, amidst and within objects and spaces that are particularly redolent of community (or lack of it.) Even the quality or quantity of childrens’ toys left out in shared backyards speaks of relative prosperity, diversity, or equity. Small marks on door frames or walls, or the presence of shared plants grown on public spaces like streets, or the residue of a regular maintenance regime, tell stories of permissions and rights, equity and access. Patterns of cultural production — of arts, crafts, and making — can be spotted in both formal and informal settings, growing in the cracks between spaces deliberately set aside for creativity, as well as within them.

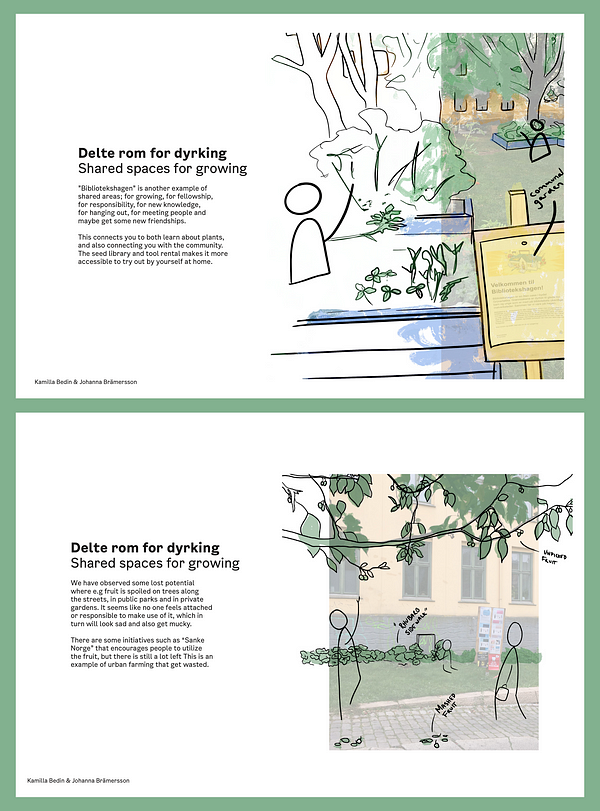

Food — growing, cooking, sharing, eating, recycling — and the diverse arrays of greenery and biodiversity beyond simply growing food, was clearly a particular focus, perhaps triggered by its rich potential for urban innovation, and the uneven patterning of these various aspects to food across the neighbourhoods the students engaged with.

What if? Propositions for everyday life in Oslo neighbourhoods

The propositions draw from the seeds of the observations in identifiable ways. We can glimpse those observations of food culture, green infrastructure, mobility, shared space, housing and urban development, and so on, but each is reframed, and conveyed via narrative-led ideas. The sketches are richer, the stories fuller, yet they remain tantalising glimpses. They are deliberately open, incomplete, capable of being recombined, reproduced and re-made. As Saskia Sassen (2012) notes, “Cities are complex systems. But they are incomplete systems. In this incompleteness lies the possibility of making — making the urban, the political, the civic, a history.”

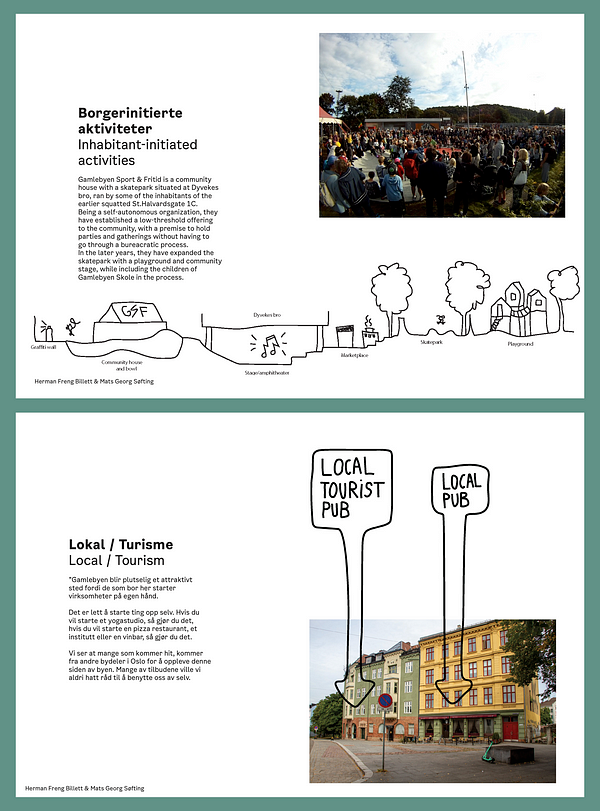

Here we see playful, critical and speculative propositions played out alongside simple, useful everyday interventions. The formats for innovation range from apps to community meetings, new types of urban design or mobility systems, plaques and prototypes and playgrounds, sports grounds and streets …

They address questions of intergenerational living, inclusivity, citizen participation, urban regeneration, safety, equity, sustainability and biodiversity… In one narrative, they implicitly address a ‘more-than-human’ perspective, by taking a cat’s eye-view through a neighbourhood.

The ideas both directly and indirectly address the role, positioning, and capabilities of the municipality, amidst the shifting relationships around social contracts, social infrastructures and technologies.

Overall, there is meaningful and considered critique here, but also a positive, progressive sensibility which absolutely conveys a sense of possible futures, of a re-framed everyday, of the sensibilities and social infrastructures of neighbourhoods in a possible future Oslo.

The Oslo Futures Catalogue: A portfolio of glimpses of possible neighbourhoods in an innovative Oslo

Download the catalogue here

You can download a copy of the Oslo Futures Catalogue v1 (PDF) here. You can also read an accompanying ‘making of’ article on which goes into the methods taught and practices on the course, with some reflections on the students’ work.

References

- Chachra, D. (2021) «Care at scale». Available at: https://comment.org/care-at-scale/ (Accessed: 8.12.2021).

- Easterling, K. (2021). Medium Design: Knowing How to Work the World. London: Verso.

- Easterling, K. (2014). Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London: Verso.

- Eno, B. (2021). «Design principles for the street». Available at: https://medium.com/dark-matter-and-trojan-horses/working-with-brian-eno-on-design-principles-for-streets-cf873b039c9f (Accessed: 8.12.2021).

- Hendren, S. (2020). What can a body do? New York: Riverhead Books.

- Highmore, B. (2013), Playgrounds and Bombsites: Postwar Britain’s Ruined Landscapes, Cultural Politics 1 November 2013; 9 (3): 323–336. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/17432197-2347009

- Hill, D. (2019). «Strategic design for public purpose». Available at: https://medium.com/iipp-blog/strategic-design-for-public-purpose-33c3899dba5e (Accessed: 8.12.2021).

- Hood, W. & Tada, G. M. (2020). Black landscapes matter. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people. New York: Crown

- Latham, A, Layton, J. (2019) «Social infrastructure and the public life of cities: Studying urban sociality and public spaces». Geography Compass. 2019; 13:e12444. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12444

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Malden: Blackwell.

- Mazzucato, M. (2013). The Entrepreneurial State. Anthem Press/Penguin Books.

- Sassen S. (2012). «Cities: A Window into Larger and Smaller Worlds». European Educational Research Journal. 2012;11(1):1–10. doi:10.2304/eerj.2012.11.1.1

- Venturi, R., Scott-Brown, D. & Izenour, S. (1972) Learning from Las Vegas. MIT Press.

Einar Sneve Martinussen is Associate professor and Chair of Interaction design at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design. Dan Hill is Professor (II) at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design and Director of Strategic Design at Vinnova, the Swedish government’s innovation agency. Ted Matthews is Associate professor and Chair of Service design at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design. Aleksandra Zamarajeva Fischer is Assistant professor at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design.

Leave a comment