On the role of design-led agencies that can work as cement between bricks, allowing systemic responses to systemic challenges, and in particular the case of ArkDes within Sweden’s research and innovation landscape

In my recent book Designing Missions, I frequently return to the idea that our complex shared challenges cannot be easily addressed by our typical democratic structures. The systemic nature of these challenges means that the well-insulated silos in, for example, the Swedish governance frameworks, enshrined in constitutions and founding documents, and baked into organisational culture, cannot address problems, or opportunities, that now awkwardly sit in the cracks between these structures.

That this applies to the most pressing, and interesting, challenges—such as the climate and biodiversity crises, or those of social justice, public health, and diverse cultural identities—does not make it any more likely that our institutions can suture together their activities and ambits to address widening wounds in environmental and social fabric. These challenges arrive unheeded in mundane everyday incursions like e-scooters, lab-grown meat, circular fashion, plastic fishing nets, food waste, electric charge points, e-commerce, or energy microgrids, each a manifestation of the sweeping, broader brushstroke challenges that define our age. Full of promise and pitfall, they expose perverse incentives and conflicting goals, and tend to provoke oversight, ignorance, confusion, or knee-jerk reaction.

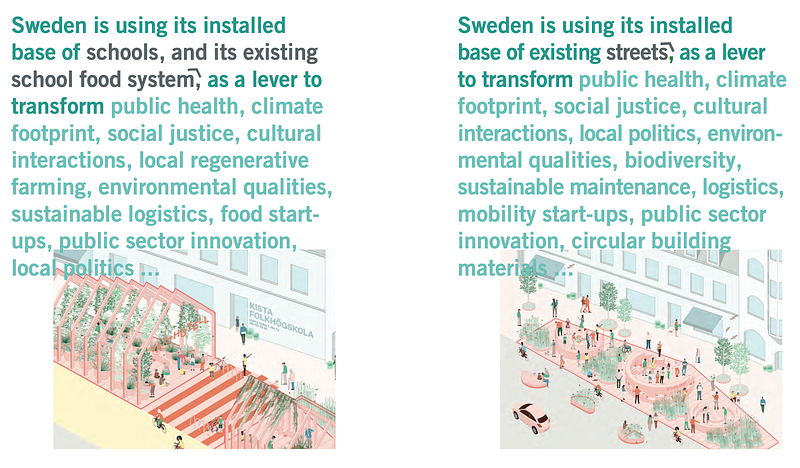

So the missions my colleagues and I helped design and activate in Sweden were in effect simply ways of aligning actors through action around these shared challenges, with numerous organisations, public, private, and third sector, working together to collectively address challenges—urban mobility, shared space, public health, food resilience, diverse cultures—each mission organisation effectively formed in the shape and dynamics of the challenge. I sometimes imagined we were cosplaying the ideal composition and culture of organisation, actually mirroring the systemic nature of challenge itself.

Systemic challenges require systemic responses, after all.

The mission must map onto the systems most directly involved, irrespective of formal organisation. This harks back to an insight my colleague Bryan Boyer visualised neatly back in Helsinki Design Lab days, describing how a cultural incursion—in this case, Helsinki’s first street food trucks—sat across and between the gaps in Helsinki’s governance.

Put simply, in another context, a Ministry for Health cannot really ‘solve for’ health, as health is diminished or created upstream, in the work of other ministries (planning, environment, housing, transport, education, food, etc), as well as municipal and regional governments, often out of reach. But the missions for mobility and food, playing out in systems like schools and streets, can address multiple systems at the same time, upstream and downstream.

That approach requires agencies that can work in the gaps within and across the existing systems of government, industry and society, with legitimacy, trust, public purpose, and shared motivation.

It requires agencies that can host and cultivate a certain types of expertise: integrative capabilities; systemic thinking; multidisciplinary creative collaboration; applied and action research; project delivery; a comfort with questions that are uncertain, ambiguous, and concern qualities as much as quantities; a range of formats and activities that make ambiguous challenges tangible; a way of getting ideas out in public…

Put simply, I think of this as an ability to hold up complex questions in public. Many of these characteristics happen to be common to design, or a design-led culture, or strategic design—although they are not exclusive to design, of course.

There are not so many of these agencies around, at least in most governments. Vinnova is one of them, and the capabilities we were able to draw together from across the organisation combined to form many of these characteristics. Yet equally, as we discovered at Finland’s SITRA, Vinnova’s culture had often, though not always, been that of a funding agency, and although it could ‘raise its head’ in public straightforwardly enough, it was not often used to working in public, at least not directly. Its primary role had been to work with, and enable, others. We had moved that culture forward, to demonstrate collaboration in and with projects and partners as well as funding them, but culture is a sticky substance.

So we needed a partner, and we found them in the form of ArkDes, the Swedish government’s national centre for architecture and design. Vinnova and ArkDes could work together on funding and delivery, facilitation and execution, design and discourse, coordination and communication. Just as Vinnova had sometimes been characterised as a funding agency but was more than that, ArkDes had sometimes been stereotyped as a museum, but was also much more than that. As a Swedish myndighet (state agency), ArkDes had the democratic qualities described above, and worked within a clear policy framework. Yet they could also be nimble, moving across the system, with nodes dotted across the country, and with a perhaps unique capability for aligning design with discourse, curating stakeholders as well as artefacts, flowing research into exhibition.

I’ve frequently written about ArkDes exhibitions, each of which exemplify this capability for taking complex questions—“What might be a new Nordic model’s relationship with public life, architecture, and diverse cultural identities?” or, “How might we live as part of urban nature, not as if separate to it?”—and making tangible these questions through inventive curation, engaged public discourse, and thoughtful exhibition. Their exhibitions on contemporary Swedish questions—Public Luxury, Infield, and Utomhusverket 2021—have been formative for me and many others.

Yet since 2017, under the leadership of director Kieran Long, ArkDes had also rebooted and reimagined its Think Tank function, which is a core part of its function (its uppdrag in Swedish, or state-prescribed mission).

https://arkdes.se/en/arkdes-think-tank/

ArkDes happens to have a museum—handy!—but it is formally the state’s official home of architecture and design, and thus ArkDes Think Tank has as much in common with Design Council as Design Museum—or is a hybrid of these two types (just as the latter now runs a Future Observatory, a national agenda for design research). And yet powerfully, ArkDes is actually part of the state apparatus, at least in the interestingly loose-fit Swedish government structure, in a way that these other councils and museums are usually not.

I’m fascinated by these ‘agencies in the gaps’, particularly those with a design-led culture and capability, enabling them to constantly reframe questions in public. As a design leader, it’s almost always my goal to try to make them. As a collaborator, I’m always looking to work with them. Such agencies can function as ‘the cement between the bricks’ of the existing system, and in these various transitions, it may be that we need rather more cement than bricks at this point.

Having worked with ArkDes intensively during my time as a director at Vinnova, on both the globally-recognised Street Moves project as well as the Swedish response to New European Bauhaus, Visioner: i Norr, alongside numerous other events and collaborations, what follows are my reflections on their positioning in the Swedish research and innovation system, as well as the landscape of public life.

ArkDes as an agency for questions

ArkDes occupies a uniquely productive position in Sweden’s research and innovation infrastructure. Embodying design’s particular capabilities for understanding, translation, application, synthesis, engagement and a systems-based approach, ArkDes forms the connective tissue between challenges and places, between policy and practice, and between the various well-insulated and separated layers of the Swedish system.

https://arkdes.se/en/arkdes-think-tank/

Their positioning in this system, and the particular skills and experiences of their staff, enables ArkDes to meaningfully hold questions in public. As a myndighet (government agency), they can do this legitimately, in a way that private consultancies cannot. As a national centre for design and architecture, they can do this with clarity, imagination and systemic integration, connecting those questions together with people and place in a way that other disciplines do not. As an organisation with a curatorial and public engagement function, they are unique amongst agencies in their ability to powerfully connect these complex research questions to the public, and document their interactions with the public sphere, in a way that other government agencies do not.

From 2017 onwards, the work of ArkDes, and especially ArkDes Think Tank, has helped till the soil of Sweden’s innovation system for a new form of engaged research in practice. Both Street Moves and Visioner: i Norr show this theory in practice. ArkDes were crucial to the success of the former, known globally as part of the ‘One-Minute City’ approach to Swedish streets, driving forward forms of participant action research and occupying the nebulous yet powerful space connecting industry, academia and society.

They helped produce original research, translated their insights into interventions in public, connecting actors like Stockholms stad and Region Västra Götaland, Volvo Cars and Voi scooters, Vinnova and Transportstyrelsen (Swedish Transport Agency), and many others. These interventions were then managed, evaluated and documented, with the built-out Street Moves kit effectively becoming a ‘platform for asking questions in public’, now rolling across the country. These might be technical questions (“How do we handle charge-points for electric cars?” “How do we better coordinate private e-commerce deliveries in public spaces?”), political questions (“How will people make decisions about, and care for and maintain, their own shared public spaces?”), environmental questions (“How do we share our cities with other kinds of nature?” “How is zero-carbon shared and active transport balanced with private desires and needs?”), or cultural questions (“What do people desire from their cities?” “How might our streets be theatres for public life rather than utilitarian thoroughfares for transport?”)

ArkDes not only designed and produced this research platform, as a key new component of Sweden’s research infrastructure, but communicated it so thoroughly and inventively that it became perhaps the highest profile Vinnova-funded research and innovation project in recent history (and effectively in inverse proportion to its actual budget!). This engagement work is not simply promotion, but part of creating a democratic social movement across Sweden’s systems, which is a research activity in its own right. The emphasis on ‘making things happen’, through diverse means, again reveals ArkDes’s generative position within the Swedish research and innovation system.

Visioner: i Norr works in similar ways, indicating how such approaches can connect national strategic initiatives and political objectives with local democracy and imagination, ensuring again this balance between quantitative and qualitative questions and insights. The work that ArkDes coordinated, for and with Vinnova and a slew of other agencies, took the questions implicit in the New European Bauhaus’s possibilities and made them tangible, engaged and engaging. Facilitating and guiding participative action to figure out the future of the North, not via the abstracted and sluggish processes of planning but through multidisciplinary teams working on the ground, indicates a future for not only design research but policymaking and governance generally.

These actions sit alongside the ArkDes Fellowship and Open Call programme, each tuned to lifting Sweden’s design scene to engage with research, and in return, for research and innovation to engage with design’s facility for imagination and engagement.

Exhibition formats like Infield, and Utomhusverket 2021 place the biggest questions of our time — such as, how might we meaningfully live as part of regenerative natural environment, not separate to it? — in a context which allows the public, including the public sector, to directly encounter the question, explore it, understand it, and reflect upon their meaning.

Even their historical research-led exhibitions — on Kiruna and Sigurd Lewerentz — re-frame formative aspects of Swedish culture for today’s concerns. These exhibitions are based on significant archival and design research, efforts that are transformed by the rigour required for translation into public display and discourse.

This is an important but underused and under-theorised aspect of applied research. We will not discover how to reimagine and rebuild our world through distanced academic research, separated from society and siloed within the academy. (I say this as a professor).

We need engaged, ‘charged environments’ in which political, technical and cultural questions come together holistically in public, aligning public, private and third sector in new ways. Academia can produce meaningful inputs into those environments, but cannot usually create these hybridised accessible melting pots of systems and cultures through which we can explore what our greatest challenges might mean, collectively. Brian Eno suggests that cultural production uniquely enables us to experience possible futures. How interesting to have research and policy explored in such charged environments?

“When you go into a gallery, you might see a most shocking picture. But actually you can leave the gallery … So one of the things about art is it offers a safe place for you to have quite extreme and rather dangerous feelings… Art has a kind of role there as a simulator. It offers you these simulated worlds … None of us are at all expert on everything that’s happening. So we need ways of keeping in synch, of remaining coherent.”—Brian Eno

Equally, possible solutions derived from academia cannot simply be emailed to society to be ‘actioned’. Instead, we need these translating layers of applied research, innovation and imagination to allow society to encounter societal ideas and technical invention together, as unified experiences, and within a democratic context. Within these formats, advanced research can be placed in the public domain.

This aspect is key to mission-oriented innovation, as described in my own writing about these projects, for Vinnova’s policy guides to missions, as well as the framing provided by both Mariana Mazzucato and the European Commission.

The Nordic region is perhaps unique in this respect, in that its political culture supports this form of multi-layered collaboration, and ArkDes is unique within the region as a government agency capable of embodying and promulgating that innovation work inventively, as virtually all our major challenges play out in our approach to our designed living environmnets.

ArkDes can do this as an agency capable of moving across much of that system, as the cement between the bricks of multi-actor entities like Rådet för hållbara städer (Council for Sustainable Cities), as well as its network of nodes embedded in key regional centres. It can translate a policy framework like Politik för gestaltad livsmiljö (Policy for a Designed Living Environment) into practice, into place, and in collaboration.

But ArkDes can also do this because this is what design and architecture does. In a time defined by uncertainty, design’s comfort with the ambiguity of open-ended and complex research questions is incredibly valuable. For design and architecture reveal and shape our shared perspectives and agendas. They take shape in our approaches to affordable housing, preventative health, inclusive social and cultural infrastructures, resilient and culturally diverse neighbourhoods, post-pandemic cities and regenerative landscapes. They impact the technologies, infrastructures and everyday practices that become our future living environments. These challenges are messy and uncertain, yet this is precisely why a design-led agency that can work in the gaps, and research, reframe and reveal these questions in public may be so valuable.

As the architectural historian Robin Evans suggested, perhaps architecture and design “occupies the most uncertain, negotiable position of all, along the main thoroughfare between ideas and things.” ArkDes’s position in Sweden’s research and innovation system, as evidenced through its internationally-recognised work of the last few years, stretches precisely along this richly patterned thoroughfare, connecting the ideas emanating from research into the innovative ‘things’ of industry, society, environment and place. That it can do this in public too, with a nimble approach to connecting systems together with legitimacy, imagination, and verve, makes ArkDes one of the key components of the Sweden’s research and innovation toolkit.

Ed. This is first of an ongoing series on organisational forms, cultures and structures capable of meaningful strategic design and systems design, entities designed to address the shared complex challenges that define our time.

Leave a comment