Help build this collection of shared, open research about some of the multiple and diverse forms of value that retrofitting our streets might produce

This is something of an experiment. As part of our ongoing work at Vinnova funding and collaborating on new research and innovation projects around streets, we are also collating existing research. We want to better understand the various forms of value that might be unlocked by transforming our streets, quantifying specific outcomes for health value, environmental value, social value, economic value and beyond.

The point is to provide countervailing data, insights, and perspectives to counterpoint, complement, and sometimes contradict the narrowly technical, traffic planning-led decision-making cultures and tools that currently tend to define how streets are designed and managed. We need to enrich that culture with other people, other actions, other models, other philosophies—but other data too.

We want to demonstrate and discuss these broad and diverse forms of value that have been actively suppressed in our streets (and other public spaces). We need to engage decision-makers at all levels, from mayors and citizens to planners and policy-makers. In doing so, we may be able to help make better tools for understanding, designing, and governing urban environments like streets, as we try to shift them from car park to park, from garage to garden, from mobility-space to meeting place. Currently, shared public spaces like streets tend to be designed, operated and measured in terms of narrow quantifiable tools, datasets, and frameworks, oriented around mobility questions—and usually, to be clear, around extractive, destructive, and patriarchal car-based cultures.

But in describing and discussing how the street can instead produce health, biodiversity, culture, justice, social fabric, environment and equivalent, we may find a way of usefully and carefully colliding the various disparate layers of governance—’vertically’ siloed municipal, regional, and national, and ‘horizontally’ via discipline or ambit—around the shared space of the street. Pulling this data together into one place helps demonstrate that each is implicated in producing the street, and that the decisions of each interact directly and indirectly with the others. By using the street as a fulcrum for this joined-up conversation, we are able to collapse these layers together, opening up the possibility of systemic change. It allows us to ask more fundamental questions: What is the street really about? What is the street for? What does it do, for whom or what?

In simpler terms, it helps create a joined-up conversation. It underscores why we might want to stand in a street in Stockholm with a representative of regional government (which runs healthcare in Stockholm region) and point to a tree (which ‘belongs to’ municipal government) and state “That tree is a health worker.” (Which it is). “Can your healthcare budget pay for the health work that it is doing? Can your healthcare budget invest in trees?” As those trees tend to ‘sit’ in the deliberately-separated urban design, environment, and street maintenance budgets and departments of the municipal government, this would be a powerful act, potentially unlocking a joined-up, care-based and upstream approach (combining both horizontal and vertical ‘silos’, in an approach sometimes known as ‘total budgeting’.) It helps us invest in health-producing environments, rather than having to pick up the pieces with hospitals, later on. (The conversation is not enough to motivate that change in itself, any more than the data is, but both will help.)

This does not look to relegate the profoundly rich value of a tree, as with the subservient ‘ecosystem services’ model—something of a dead-end, from a genuinely systemic, cultural, or more-than-human point-of-view; trees are not a mere service to us ‘masters’, but complex living intelligences. But it does at least mean we can start joining up these perspectives around the rich realities of place rather than the awkward happenstance of bureaucratic organisation. In doing so, we need to understand the myriad kinds of value that a joined-up approach could produce. That research exists; it is just rarely brought together in this way, with this intent.

It may be the ‘conversation in the street’ that is perhaps the most powerful aspect here, as it is enacted, interactive, embodied, even agonistic. But the shared view of disparate data about value, as well as the quietly potent prototypes themselves, combine to help shift the needle on systemic change, addressing multiple leverage points, as well as providing the excuse for the conversation in the first place (acting as the Macguffin, perhaps.)

There is a wealth of research indicating these rich streams of value around health, environment and justice, but it is rarely brought to bear coherently around shared public spaces like streets. As we look to transform those streets into more diverse spaces, more akin to a garden or a piazza, research about community gardens swings into view, about human interactions with nature, about social value and growing food together, about learning and outdoor classrooms, about the complexity of trees—all could be now in play around streets. And we have every reason to bring this data together.

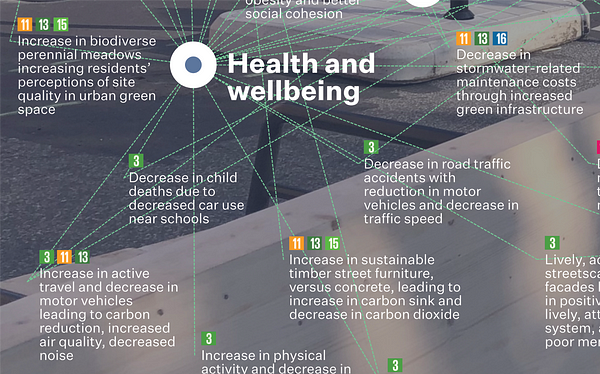

For our Streets mission in Sweden, I made a quick sketch (below) to suggest the various forms of value that the Street Moves prototypes put on the table. I’ve loosely tagged the outcomes against United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, as they provide the longer-term high-level ‘steering’ for government actions in Sweden, as in most other countries. I’ve loosely grouped them into ‘pools’ of outcome, and suggested some relationships. The outcomes are not tagged directly to aspects of the intervention but the visualisation style suggests that they might be. It’s a relatively complex image, but in reality, of course, the mapping would be way more complex, and with many more forms of outcome.

A shared document about the shared value of shared spaces

Opening up what the street can be about opens up the range of research that could be deployed. So I would like your help in adding to, and refining this shared array of research! Over the last year, I’ve collated hundreds of academic research papers and articles in a shared Google Doc which I’m opening up here. You can add to, and edit, this research. As this is a shared open document about shared spaces, you should feel free to use it in your projects and discussions too. Here it is:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1UYqhnVBv_Stqaz8Mn_ONDIpM0bDoR57N6DVi47Lp9jU/edit?usp=sharing

I have a backup copy of the openly-shared document, but please try not to destroy or compromise too much! The tragedy of the commons is often a myth, so let’s try to not to reinforce the myth! Particularly about a subject that involves a form of commons, after all.

There are instructions and suggestions in the document, but essentially, I’d appreciate it if you follow this straightforward format:

- Title of article (ideally using Heading 4 paragraph style to help indexing)

- Synopsis, abstract, or excerpt (indicating relevant insights and findings)

- Reference (preferably a standard academic citation format) including link to original research, DOI, or referring article)

- Hashtags (open, so try to build on existing hashtags where possible

And try to paste the reference into one of the high-level categories—health, environment, social, economic, or combined outcomes—and ideally the lower level groupings. But I’ll do ‘gardening’, periodically, so don’t worry too much. Feel free to leave comments. There’s an index at the end, as well as a section to add notes on tools and methods. (I’m aware I could probably build a database for this, in Notion or Airtable or somesuch, and we probably will at some point. But for now, I’m using a Google Doc as it seems the lowest possible bar, not letting ‘perfect’ be the enemy of ‘good enough to get something going’.)

I hope I’m not breaking any ethical research guidelines here (though let me know if I am), as it’s just listing existing research. And the idea is simple. You can use the list; we (Vinnova, the Swedish government’s innovation agency) will use the list to help inform our projects building up alternative ‘value models’ for streets, complementing our existing work.

A note on quantifying a thing with qualities

This particular work deliberately concerns quantifiable outcomes, but that does not mean we are trying to simply ‘quantify streets’. My work has been largely concerned with the opposite: the un-quantifiable, the qualitative, the cultural rather than technical, even though it has often involved technology, buildings, spaces, and quite tangible systems and interventions. Working with cities, I find more value in qualitative approaches, drawn from history, culture, memory, narrative, aesthetics, sensation¹ .

There are people who do not like a place because it is associated with some ominous moment in their lives; others attribute an auspicious character to a place. All these experiences, their sum, constitute the city.

— Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City (1982)

There’s a clear danger that attempts to quantify the value of complex urban environments tend towards a functionalist view of such things. And functionalist approaches to understanding cities tend towards functionalist approaches to planning cities, to governing cities. An quantifiable approach to understanding cities can only really capture that which is overly quantifiable, leading one into a terrain dominated by narrow numeric metrics, framed by logics like efficiency or control—and as I’ve suggested many times, cities are not about efficiency and control at all. Instead, if cities are ‘about’ anything, they are about culture, conviviality, community … perspectives that are largely beyond quantification. Reflecting on a dinner I once had with Prof. Geoffrey West, amongst others, at a discussion assessing neuroscience and what West described as a potential ‘science of cities’, and which he characterised as “quantified, mathematised and predictive”, I ended up concluding that “the subjectivity of cities is what makes them so compelling, perhaps.” It seems to me that there are hard limits to the usefulness of the ‘science of cities’ approach.

We must also be aware of playing by someone else’s rules. I rarely want to get into a battle with a spreadsheet by wielding another spreadsheet. No matter how much quantified data about health, environment or social value we might present, the voices of capital might simply seem to have a bigger number. Or can simply conjure a bigger number. A handsome Internal Rate of Return could always be more appealing, and can be pumped up rather too easily. Numbers are subjective, despite claims to the contrary, and it could be that a project’s internalised logic, derived from underlying power dynamics, can simply amplify the values that appeal to, say, motorists or property developers, rather than the health or social life of those, human and otherwise, that will live and work in said project.

Equally, there is a clear flaw in using financial metrics, including price mechanisms, for something that is broadly cultural, social and political, like a street. As my colleague Mariana Mazzucato put it recently, in conversation with former Bank of England head Mark Carney, “Any green and inclusive agenda must start from the recognition that value is not the same as price, and value creation is a collective process that involves not only businesses, but also workers, public institutions and civil organisations.” I would add the natural environment to that list, as that article notes.

Mariana and colleagues have also written much about the need to handle dynamic metrics in dynamic fashion too, whereas others, like Dag Detter and Stefan Fölster, in The Public Wealth of Cities (2017), has pointed out the problem with cities not recognising the wealth they truly possess, mediate, or embody, instead seeing finance as fixed flows stuck in the rigid, impervious channels of legacy spreadsheet columns: “Public accounting focuses largely on flows, and these do not say much about the real state of the financial affairs in the public sector and nothing about wealth. For a government official or politician with a responsibility for a budget, esteem and power may be measured by the size of that flow. This mind-set assumes that assets are intimately linked to their current use, and this is why fragmentation and lack of visibility are not seen as problems in public financing.”)

Then again, my experience tells me that, in some instances, we must produce data nonetheless. This is partly because such data provides the starting point for a richer discussion: What is this project about? Could it be about this? Or this? This follows a richer understanding of data, from Morton and others, that it is something you are given, or is constructed, as a thing to work with and work at. It is something to do. Like dough, it is of little value unless it is worked into something more meaningful.

The outcome of such a discussion about data should ultimately encompass and perhaps prioritise qualitative value, unknown as well as known, un-quantifiable as well as quantifiable. Producing a broad array of potential outcomes is a token, an opening gambit, helping shift the discussion as to the ‘north star’ guiding the project or the place. Apologies for the metaphorical terrain, but as someone who apparently knew a bit about winning battles once wrote, “We cannot enter into alliances until we are acquainted with the designs of our neighbours.”

There are fascinating debates in all this, not least as some dig into entirely new methods, such as neuroscientific research, albeit perhaps simplistically playing off the idea of urban imagery versus natural imagery. Given that we are nature, what does this mean? Others rightly debunk the idea that ‘healthy doses of nature’ are the same for everyone—they are not.

Such research does not deny the basic principles of exploring multiple linked forms of value, of course. It reinforces a more diverse approach to what interactions with nature can be — not whether we should interact at all, but how — drawn from engaging with social and cultural diversity (within the One-Minute City perspective), or beyond ableism, as well as moving into more-than-human approaches.

I’m interested in these new approaches and see immense value in broadening our understanding from numerous perspectives, yet it’s important that they do not simply lead to a new form of overly functionalist approach, relegating the more slippery culture to a ‘nice-to-have’. ‘Culture’ is not something we can observe and model with brain imaging or equivalent. It is well beyond science’s reach.

Yet let’s explore what is within science’s reach by working together to share as much good quality, relevant research as possible. Here’s the doc again—please do add to it:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1UYqhnVBv_Stqaz8Mn_ONDIpM0bDoR57N6DVi47Lp9jU/edit?usp=sharing

¹ For example, to ‘get a grip’ on New York, say, we will gain rather more from Jacobs and Jay-Z, Cole and Koolhaas, Mbue and Morrison, Zorn and Zhang, Rupture and Rear Window, Hanya and Hamilton, Olalekan and Eisner, Whitehead, White and Wu-Tang than from the output of any ‘data-driven management system’. More from Baldwin, Burrington, Brennan, and Basquiat than from bullet points. More from Scorcese, Standards Manuals, Seinfeld, Sorkin and Solnit’s maps than from simplistic statistics. And frankly, more from walking around the place a lot and just having a good old look, than from almost any of the above.

Leave a comment