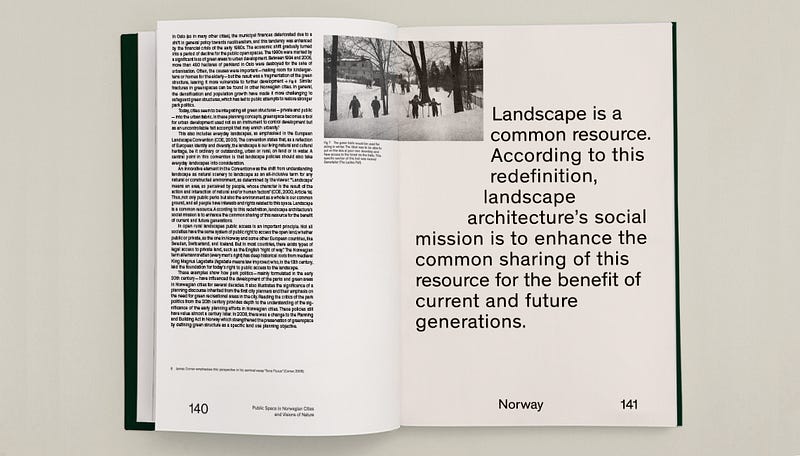

Adapting Holger Blom’s 1946 principles for Stockholm’s park programme to inform today’s street systems

In my piece unpacking Brian Eno’s design principles for for our Swedish street mission, I suggested, as an aside, that “it feels like landscape architecture, having been unfairly downplayed for decades, perhaps for obvious if unfortunate reasons, may increasingly be the most important strand of architecture moving forward, for those same reasons, reversed.”

In landscape architecture, we see a practice attuned to biodiverse environments, integrated systems and cultures, ongoing and adaptive long-term engagement, multi-species or more-than-human-centred design, and more besides. Downplaying these practices in the past means we must focus on them now.

Yet that history is littered with shining work and useful clues, but I thought I’d borrow from a quiet bit of ‘local’ work here in Stockholm, from around eight decades ago.

In 1946, the respected city architect of Stockholm, Holger Blom, became its first city gardener. (We have city architects in Sweden, and across the Nordics, but you don’t often hear of a city gardener. I suspect we will, in future, given their potential.) Blom’s impact on the built fabric of the rapidly growing post-war Stockholm was significant, as a quick browse of Digital Museum’s entry makes clear, but it’s his work beyond buildings that concerns us here.

With this new responsibility of city gardener, Blom produced a parks programme for the city, describing four paroles — or ‘public promises’ — for the parks. The programme was conveyed to the public in an illustrated leaflet distributed by mail to each household in Stockholm.

According to Thorbjörn Andersson in the excellent recent collection Green Visions: Greenspace Planning and Design in Nordic Cities, the paroles addressed the planning issue, the public health issue, the social issue, and the conservation issue, all at once, indicating clearly and precisely how integrated design patterns focused on what I would call a ‘place-type’ of social infrastructure—the park—might unlock multiple systemic outcomes. A ‘type’ like a park—or a street, a market, a garden, a library, and so on—can corral all these systems and cultures into place, in a way that is integrated, and yet entirely everyday—and could be adopted and adapted elsewhere.

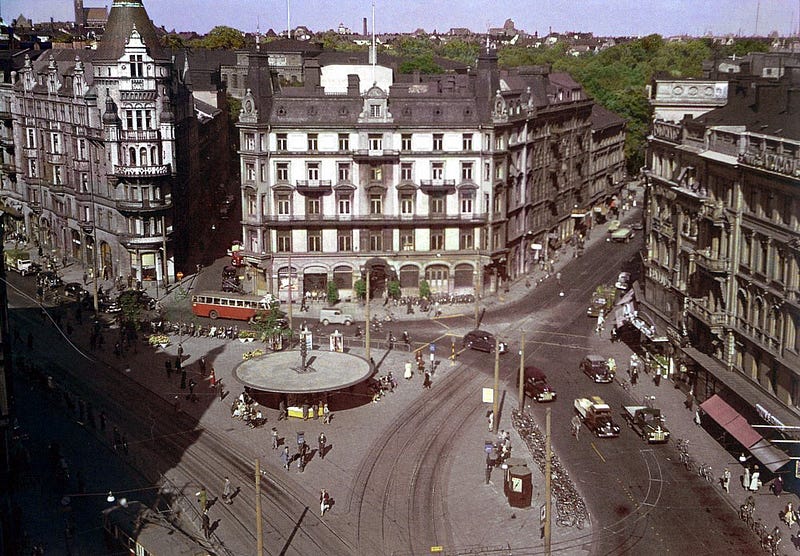

In other words, a street market in Berlin is quite different to a street market in Bogotá – but at some level they are both street markets. The place-type’s intrinsic balancing act between the cultural and environmental specificity of a place, and its universal spreadability (I’m deliberately avoiding the word ‘scaling’ here) is particularly powerful. More on this later. Here, we are interested in streets and parks.

Are we simply, as unlikely as it may seem, following in the footsteps of Prince Hermann Ludwig Heinrich von Pückler-Muskau?

For my contribution to NESTA’s Rethinking Parks programme in 2020, which closed out the essay series, I wrote The park is dead. Long live the park!. Drawing from Fumifugium in 1661, Val Plumwood’s shadow places and Ron Finley’s parking lot farms in LA, I suggested that the old segregated model of the park as ‘the lungs of the city’—a deliberate exception to the rule of grey, dirty hardscape elsewhere—must now be reversed: rather than the odd park here or there, we define parks by “flipping space inside-out such that the street itself becomes the park.”

No more ‘parks’, essentially, but the condition of parks everywhere. In that, I didn’t really mean that we should dig up Liverpool’s Birkenhead Park or Münich’s Englischer garten. Rather, we must share our ambitions for parks with everywhere else in the city, asking why these more everyday environments must be so bereft of biodiversity and conviviality, culture and nature.

This thought evokes the famous ‘Nolli map’ of Rome, produced by Giombattista Nolli, from 1736 to 1748. That kind of figure/ground reversal, asks us to draw the green and social public space of the park throughout the city, more equitably and with greater diversity, by virtue of creating streets with the same conditions as parks, oriented around intense biodiversity, play, culture, conviviality, reflection, encounter, celebration, promenade, and so on.

Existing parks could then become intensified versions of these conditions. Perhaps we follow the lead of Prince Hermann Ludwig Heinrich von Pückler-Muskau, who created Europe’s first landscape parks in the mid-1800s, which sit in a continuum between the garden close to castle—which he described as “extended living space”—and then park, proper—which he describes as “concentrated idealised nature”.

In this light, it seemed reasonable to lean on Blom’s insights for parks when now thinking streets, recognising that they could be more consciously connected, all sharing varying conditions of greenery, biodiversity and conviviality. This suggests a tapestry in green, with parks as intense idealised pockets of nature—spectacular or quiet, but concentrated either way—at the threaded intersections of thickets of green streets.

These more convivial, diverse and human-active streets become an green-yet-urban twist on von Pückler-Muskau’s “extended living spaces”, which is a perfect description of the One-Minute City thinking, where the street is a genuinely shared space for the neighbourhood around, truly public space defined by activities as diverse as people are—rather than being defined by mutually-exclusive car parking that currently tends to privatise such spaces.

And parks become more biodiverse pools of von Pückler-Muskau’s “concentrated idealised nature”. These lend themselves to true set-pieces, such as the Japanese tokubetsu meishō (places of particular beauty) or the numerous examples we might find in Nadine Olonetzky’s extraordinary compendium Inspirations: A Time Travel through Garden History. In this latter idea of “concentrated nature”, we also open up the possibility of contemporary nature-based infrastructures, whether East Kolkata Wetlands or Copenhagen’s Soul of Nørrebro park-as-flood-barrier, designed by SLA, perhaps versus the more ubiquitous Melbourne Urban Forest, which naturally follows the streetlines.

A blur between parks, gardens, and streets, reforesting our cities

In my current context, I’d described this idea almost as ‘reforesting Swedish cities’, for example, filling avenues with trees, until they begin to become the dominant character once again: this is streets as ‘the basic unit of cities’, hosting trees as the defining element of the Swedish landscape.

These sketches for Helsingborg (below), which I asked Utopia Arkiteker to do for our Streets mission with ArkDes, shows this idea of a progressive urban reforesting, using existing street networks as the basis for increasingly verdant avenues of trees, which ultimately blur stone cityscape into adjacent park.

That sketch was partly inspired by a thought I’d had looking down on one of the loveliest little streets in Södermalm, Stockholm, Katarina Bangata, in high summer.

Melbourne’s aforementioned Urban Forest Strategy begins to have a similar feel, as the extent of the tree canopy begins to suggest that we might shoot beyond the stated goal of 40% coverage, to almost joining up entirely, as if the tram cables over the streets are simply trellices-in-waiting, with the forest creating a cooling carapace over the hot streets below.

These organic approaches—less mortar, more mychorrizal—describe a flexible, shifting continuum rather than a fixed binary opposition, as per my diagram above, flowing sinuously from streets to gardens to parks, a more complex dynamic.

Ed. See this related thought on urban dynamics, regarding the idea of landscaping informational connectivity.

There are numerous reasons we might pursue this pattern for streets defined by street-trees, from public health to climate resilience to carbon sink to aesthetics. But perhaps my favourite reason comes from a conversation with Bee Urban’s Josefina Oddsberg Gustafsson, whose mission can be thought of as creating a city fit for our pollinator friends. As an aside in our chat, she mentioned to me that Swedish bees apparently like to fly along grid patterns, waggle-dancing their way in roughly straight lines, having been ‘trained’ by the tendency for rich pollination possibilities to occur in the biodiverse buffer zones which run along the edges between farmers’ fields and forests in Sweden, forming elongated loose grids. (Thus, allusions to Linda Tegg’s Infield installation.)

It’s a delicious thought that a bee-centred redesign of cities might reinforce our existing street patterns.

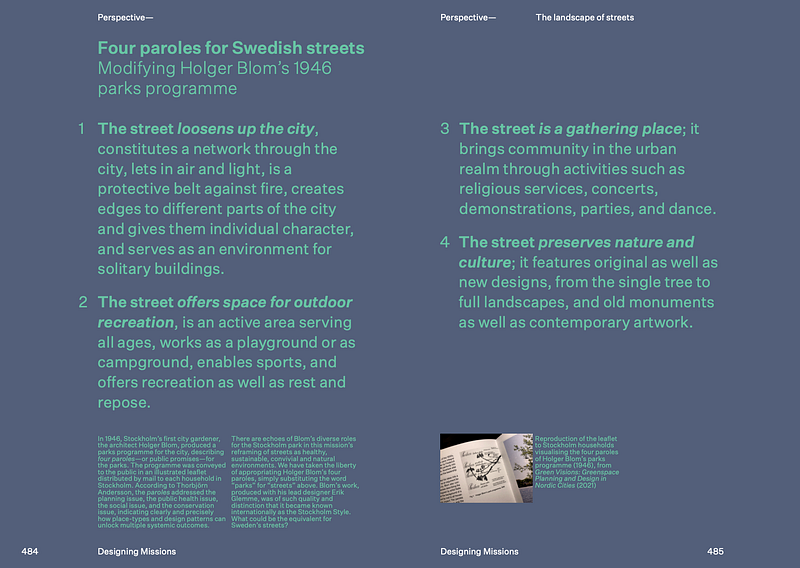

Holger Blom’s paroles, and find-and-replacing ‘streets’ for ‘parks’

Continuing my interest in shifting design principles for streets away from a traffic engineering culture, I wondered whether we could see Blom’s diverse roles for Stockholm parks as part of our mission’s reframing of streets as healthy, sustainable, convivial and natural environments.

And so I took the liberty of appropriating Holger Blom’s four paroles, simply substituting the word “parks” with the word “streets”. It goes a little like this:

- The street loosens up the city, constitutes a network through the city, lets in air and light, is a protective belt against fire, creates edges to different parts of the city and gives them individual character, and serves as an environment for solitary buildings.

- The street offers space for outdoor recreation, is an active area serving all ages, works as a playground or as campground, enables sports, and offers recreation as well as rest and repose.

- The street is a gathering place; it brings community in the urban realm through activities such as religious services, concerts, demonstrations, parties, and dance.

- The street preserves nature and culture; it features original as well as new designs, from the single tree to full landscapes, and old monuments as well as contemporary artwork.

Again, all I’ve done there is swap the word ‘street’ for the existing word ‘parks’ in Blom’s original. It works surprisingly well, I think, in terms of conjuring an idea of what streets can be about, at least in the One-Minute City sense of streets, as “extended living spaces”.

Perhaps this is not surprising. A mid-20th century urban planning sensibility placed this emphasis on parks to carry the living spaces—the ‘livsmiljö’ in Swedish, which translates to ‘living environment’—for the city and its citizens, whilst simultaneously waving through destructive car-oriented planning almost everywhere else. We cannot be so careless now. Perhaps the same set of qualities that we once looked for in parks really should be everywhere, as the list above begins to suggest. Noting my point about bees above, perhaps this reinforces the idea of a garden-centred redesign of our cities.

Just as the simple trick of ‘find-and-replacing’ the word ‘parks’ for ‘streets’ indicates, our task now is to similarly find and replace such environments in our cities beyond the text, Finding the hardscape, inert and often lifeless conditions of streets around us and Replacing with softer, adaptive, more natural, cultural and convivial diversity, bio- and otherwise.

Look at some of Blom’s choices of words:

- the street “preserves nature and culture”, suggesting an interplay between those two that Timothy Morton, Emma Marriss, Linda Tegg, or Büscher and Fletcher might extol.

- “Old and contemporary … single tree and entire landscape” suggesting both a systemic and cultural understanding of these connections

- “A gathering place for the community”, for various rituals, celebrations, and as “playground”

- And then “loosening up the city”. Loosening is particularly pleasing and powerful verb, given the cultural context and its tendency towards control, technocracy and risk-aversion. There are clear echoes of Richard Sennett’s open city thinking here. Blom suggest that the “loosening” role of parks—and so, streets, now—is to lift buildings and places to be individually diverse (also an important move here, with much homogenous building otherwise) whilst delivering clear environmental benefit (clean air, good light—and now we’d call out biodiversity regeneration). The reference to “firebreaks” may initially seem relevant only in a post-War context (not that Stockholm was physically engaged in that, but was close enough to the damage wrought to the south, and with many old timber buildings around). But perhaps now we might see it as presaging Tokyo’s firebreak urbanism model, and maybe—a long bow being drawn—of relevance again in an imminent age of wildfires.

A new Swedish style, built from the material of the old

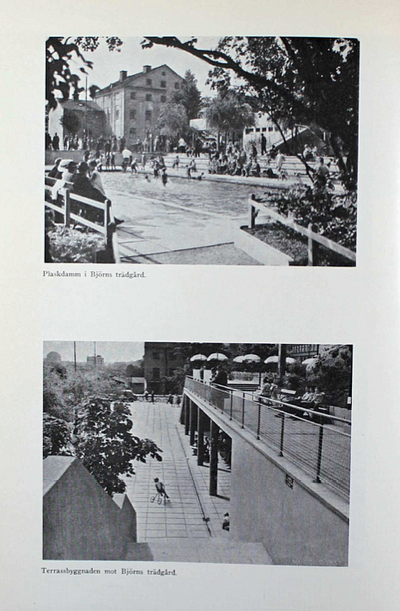

Blom’s work with parks and landscapes, produced with his lead designer Erik Glemme and Danish-Swedish architect and sculptor Egon Möller-Nielsen, was of such quality and distinction that it became known internationally as the Stockholm Style.

Blom’s impact is still discernible in today’s Stockholm. Designing from the scale of park benches up to entire districts—almost as if following Ernesto Nathan Rogers’ notion of designing “from the spoon to the city”—Blom’s work can be experienced in playgrounds and parks, bus stops and and gardens—as if the directive from the city officials was to let a thousand flowers Blom (sorry).

Some of his work, such as the city’s first Mjölkbar at Björns Trädgård (1937) in Södermalm and the original mushroom shelter (‘Svampen’, also 1937) at Stureplan, are defining works of Stockholm modernism—even if the milk-bar site is now a pale echo of Blom’s elegant original, and Svampen was demolished and rebuilt. Tegnerlunden, by Blom and Glemme (1940), in central Stockholm remains a strong example of his ability to conjure a natural landscape out of relatively small and onfined urban pockets. This approach to a naturalistic yet distinctly urban landscape architecture may be the true legacy of Blom’s parks department at that point, yet we can learn a lot from the multidisciplinary practice and systems thinking, as well as public luxury instinct, at work in these various ‘place-types’ of humble social infrastructure.

By building on the work of his predecessor, Oswald Almqvist, Blom had produced the first modern park system in Europe (Sweden had previously inaugurated Europe’s first national park, in 1909, after ‘lobbying’ work by the political refugee and explorer Baron Adolf Erik von Nordenskiöld).

We might argue, of course, that another very different ‘Swedish style’ was emerging alongside Blom’s parks, at much larger scale, as by 1955 Sweden was becoming Europe’s most car-dense nation, and creating the hardscape, unsustainable and unhealthy environment familiar to so many countries, which directly mitigated against conviviality and culture. Sweden is no different in this respect, despite Blom’s interventions. What might we learn from this?

Interestingly, Blom had also created much of this park system directly from the material of the growing post-war city, building parks and playgrounds from the earthy spoils of Stockholm’s subway expansion, almost in an alchemical act of conjuring play and culture from construction spill. Could excavating today’s hardscape streets provide similar civic green spoils, as with my suggestion that we might similarly ‘daylight’ Melbourne’s?

As with Walter Hood and Grace Mitchell Tada’s suggestion that landscape architecture can “activate the mundane is an opportunity to see and experience the beauty and utility of the things in our life”, perhaps we might now try to perform a similar conjuring act, constructing conviviality and culture from the mundane, often inert streets that surround us.

Blom’s principles, when transposed to streets as I suggest above, indicate how streets might loosen up the city, offering spaces for outdoor conviviality, and everyday play and culture, as well as acting as gathering places for the community for rituals and celebrations, and preserving nature and culture. Not a bad set of directions.

What could be the equivalent of Blom’s framework for Sweden’s streets? What is the New Stockholm Style there, now fit for our age? And what of Gothenburg, Malmö, Umeå? How can we ‘find-and-replace’ one urban element for another, more potent? Scanning Blom’s modified paroles — as with Eno’s rules-of-(green)-thumb — perhaps gives us a clue.

Leave a comment