A recent thought on blurring streets and parks in Stockholm echoes an older thought on spatially shaping connectivity and informational intensity on Barangaroo, Sydney

In a recent piece on adapting Holger Blom’s landscaping principles from 1940s parks to today’s streets, I suggested we might think about a blurred, shifting continuum of park-like conditions—biodiverse and culturally diverse activities and environments—moving from streets to gardens to parks. This, as opposed to the traditional binary opposition between parks (‘the lungs of the city’) and streets (its hardened arteries.)

As I noted, this almost suggested a canopy forming over the city, describing something akin to how Melbourne’s Urban Forest Strategy will help protect the city against otherwise intense heat at street level, as well as giving us the numerous other benefits that street trees provide. And in that, there are also echoes of the way I imagined the density of urban fabric suturing together the spaces in Barcelona’s Ciutat Vella — what Joan Busquets called an ability for the urban environment to “reform from within”—yet via rather more benevolent trees, as opposed to stone.

Such a leafy fibrous cityscape is obviously far more appealing that Buckminster Fuller’s absurd ideas for a dome over Manhattan. (Equally absurd, by the way, is Treehugger suggesting it’s time to look at that proposal again, after a bit of snow last year. It’s. Just. Weather. Hey New York, learn to design and operate in a way that embraces the connection to weather and environment in order to become resilient. You’ll gain little from working against it. I’m looking forward to reading the recently-arrived Daniel A. Barber’s Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning to discover where this some of this aversion to the environment comes from.)

All this has an unlikely faint echo of a diagram I drew around 12 years ago. It described a possibly similar approach to digital connectivity for the Barangaroo, Sydney development I worked on—and let me just immediately recognise for the Australian audience here, that this was not an easy project to work on, as you all know.

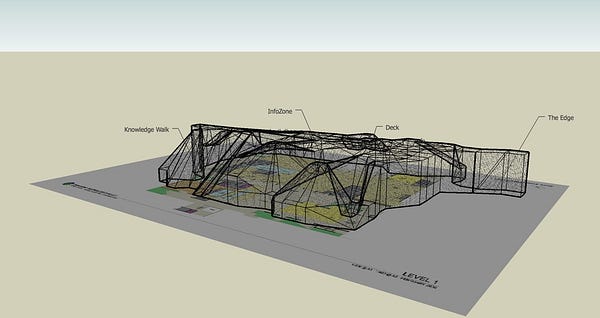

Barangaroo was intended to run from a newly-constructed, intense and hyper-connected financial services-led downtown-style environment, which might have as much in common with Singapore or Macau as the rest of Australia, through to what former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating had intended to be a waterfront park that would ‘restore’ the Sydney coastline to its pre-invasion condition. There is considerable folly inherent in both ends of that argument: certainly aspects of the ‘Macau end’, but also at the other, as if a landscape-oriented sop to the indigenous agenda would help ‘make it all better’. That argument will run and run, and is for another day.

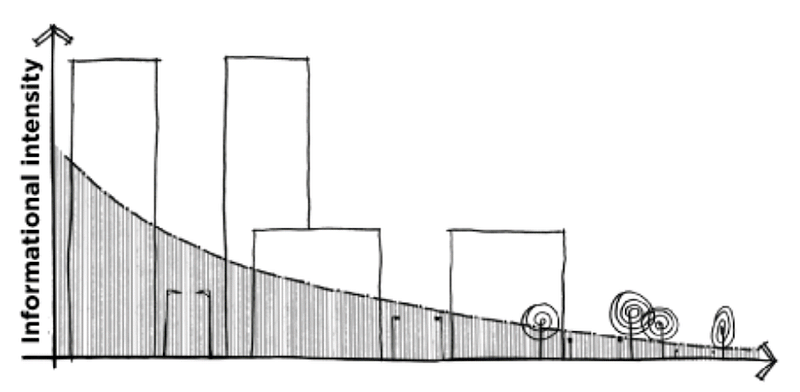

In this light, though, working with landscape and other architects on the project, from Aspect Studios to Rogers Stirk Harbour, I suggested we might try to do the opposite of what was already becoming business-as-usual then — pervasive and continuous connectivity — and instead deliberately try to reduce the connectivity in the park, as a counterpoint to the intensely-connected other end.

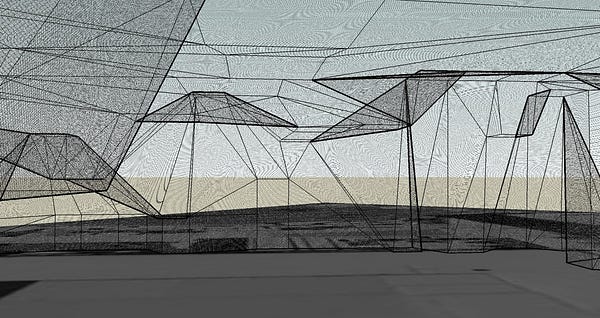

If the downtown ought to feel like Ginza, the park should be more like a glittering rockpool. If this park was truly intended to conjure a pre-colonial environment, defined by a sparkling ‘natural’ coastline painstakingly reconstructed through historical research — again leaving aside the considerable ethical issues in doing that, as well as the vanishing of the more recent history of industry and labour — then it may be a little odd to have pervasive, full-signal strength wifi and 4G there. Wouldn’t it? Shouldn’t it be a place to disconnect, at least momentarily? A moment for private reflection? Or intensely public but embodied, fully connected physically? We don’t have to populate these tumbling sandstone seashores with arrays of WiFi routers or chuck a cellphone tower in there, poorly disguised as gumtree. It’s a choice. And if it’s a choice, what’s the thought behind it?

Safe to say that this more, well, ‘poetic’ approach to connectivity didn’t exactly fly with all concerned on the project. It was not really a project suited to this kind of thinking, perhaps. Equally, this kind of thinking also has its flaws, of course: about the role and value of connectivity, about who gets to decide when you can be connected or disconnected, and about the idea of what a natural environment means at this point. Is it really ‘convivial conservation’? Would this approach be at all beneficial to stimulating broader thinking and action about focused connection, about meaningful environments? Or is it an empty gesture, half-closing the stable door long after the horse has bolted…

But I’ve been interested in this idea of ‘sanctuary spaces’ in hyper-connected environments since my work on State Library of Queensland in Brisbane, where we explored ‘fading up’ the wifi in social spaces and pulling it down in areas where physical, focused engagement with collections was the goal.

Even in 2008 it was possible to foresee some of the issues around constant connectivity, distraction and social media, well before anybody had uttered the phrases Social Dilemma, Humane Technology, or Surveillance Capitalism. Yet although informational connection is core to the question of librariness, perhaps this is an even more heightened concern in a supposedly naturalistic park, oriented around rambunctious social and physical play, or quiet, contemplative reflection.

Subsequently, my work with Punkt on their MP02 phones-not-cellphones explored similar ideas around focus and environment, giving the choice to ‘flip the switch into Punkt-mode’ to the user, ensuring little or no unintended distraction. Space Caviar’s experimental RAM House, a few years later in 2016, actually suggested ways of pulling this off technically, with radio-absorbent materials, suggesting the idea of Faraday Cages purposefully formed by constructed landscapes (Faraday Caves by the seashore?).

But conceptually, other than the ‘naturalistic’ sense of disconnecting from the internet, the idea of a dynamic, as in a piece of music, felt interesting. We being to lose interest in a piece of music that is the same loud volume continually, forever. Music has a clear sense of dynamic, defined by counterpointing loud and quiet, bright and soft, light and dark, developing complex relationships from their differences. Could the same happen with connectivity?

Maybe, maybe not, and of course connectivity is different to music — it is infrastructure rather than art form, essentially. If you go to Barangaroo now, I imagine you can indeed use TikTok standing on those naturalistic steps. Maybe that’s OK—though I wouldn’t want to second-guess Keating’s views on that.

But there seems an allusion here to this other diagram, to this idea of a dynamic — not greenery and parks everywhere, but a diversity of registers of biodiversity, shifting from loud to quiet; again, as if musical score. I still think this is interesting, and the ‘sanctuary spaces’ idea has come up on numerous projects since. It’s rarely been implemented, as far as I know. Hence sharing it here, at least, to at least prod the idea along a little. What do you think?

Leave a comment